E-flite Mystique RES 2.9m ARF User Manual

Page 38

38

Evening thermals are typically large, warm air masses

meandering through the sky. They are usually very

smooth with soft edges. The middle of the day (noon to

4:00 p.m.) is when the thermals are at their strongest.

The flip side to this is that with every thermal there

is also sink. Sink is the surrounding air that is left by

the thermal leaving the ground. Typically sink is on the

downwind side of the thermal. Sink is created when

warm, rising air is displaced by colder, descending air.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, because where there

is sink, there is also lift close by. The trick is to find lift

before you have to land.

Thermals can also start at ground level. And if you are

skillful enough, you can catch a thermal from 20 or so

feet and ride it up to 1000’.

how to catch a thermal

One of the best pieces of advice we could give you is to

always have a planned search pattern when looking for

thermals. Even the most seasoned thermal competition

pilots will have a search plan before launching. This is

one of the basics of thermal flying. If you have a plan

based on sound thermal logic, chances are you will more

than likely find a thermal.

As thermals don’t typically stay in the same location

for long, you can’t just go to the last place you found a

thermal. Often we hear pilots say, “Fly over those trees.

There is always lift there.” In reality, this may have

been a location where they did in fact find a thermal;

however, it may not always be there. Our advice is to

have a planned search pattern, ensuring you cover as

much ground as the model is capable of before landing.

Many people just fly straight upwind. This is ok, yet

we would suggest working in an “S” pattern, which will

increase your search pattern. You can still keep working

your model upwind; however, you are going to cover a

lot more sky for the same loss of height if you work your

model in an “S” type flight pattern. You don’t have to go

out of sight each way either; perhaps 300’ either side

of center will be sufficient. Also, be on the lookout for

ground markers. You can’t see thermals, yet you can

see things that identify them. These are your ground

markers.

Wind direction and velocity are also great thermal

indicators. Often colder, descending air fills in the hole

that a thermal leaves as it moves along the ground.

Traveling downwind of a cooler air mass might be a good

indication of where a thermal may be. If the wind has

been steady in your face and you feel a distinct change

of direction, perhaps shifting more from your left, then

there is a good chance that the thermal is to your right

and slightly behind you. The same would apply if the

wind shifted to blow from the right, as there would be a

good chance that the thermal is to your left and slightly

behind you. If you feel the wind strength increase, yet

stay blowing straight into your face, then the thermal is

directly behind you. Finally, if the wind reduces in velocity,

or even stops from a steady breeze, then the thermal

is either ahead of you or right above you. Basically, the

thermal will be where the wind is blowing toward. Always

pay attention to the general wind direction and look for

changes in both its direction and velocity for signs of

thermals.

Other good indicators are birds. Many birds are capable

of soaring, and you will often see them soaring on the

thermals. Before launching, always check for birds. Pay

close attention to how they are flying. If they are flapping

hard, chances are they are also looking for lift. If they

are soaring without flapping, then there is a good chance

they are in lift. Birds also like to feed on small insects.

As thermals initiate from the ground, birds will suck up

small insects sent into the air. A circling bird is a great

sign that there is lift.

Another idea that works well is to fly over areas that

are darker, often a freshly ploughed field, a parking lot,

dirt, or anything with a dark color. Since darker colors

absorb more heat, they could be a good source of

generating thermals. One little test you may like to do

is to paint various colors on a sheet of paper and place

them in the sun. After 30 minutes or so, go and check

which colors absorb the most heat. Once you know what

colors make the most heat, look for natural areas on

the ground that match these colors and use those as

locations for thermal hunting. While these are just a few

helpful search options for you, we are confident that as

your knowledge and understanding of thermals improve,

you will start to have your own special thermal hunting

locations.

what to do when you find a thermal

Probably the first thing you need to be absolutely sure

of is if you are in lift. Often a sailplane may find what we

call a stick thermal. It’s a tongue-in-cheek term meaning

you may have been carrying some additional speed

and the model will climb by pulling elevator. One of the

best signals you will see when the model is truly in lift

is it will slightly speed up and the nose of the aircraft

will be down slightly. The model will feel more agile and

responsive. Once you have found your lift and you’re sure

it is lift, start circling in a moderate circle, about a 50–

75’ radius. The next thing you need to do to determine

is how big the thermal is. Once circling, you may notice

that your model may drop on one side of the thermal

and be more buoyant on the other. The perimeters of

most thermals are clearly marked by downward flowing

air. If you have seen an atomic bomb cloud, then this is

a good visual for you to understand what a thermal can

look like. The center has fast, rising air and the outside

has downward, rolling air, often known as the edge of the

thermal, or the thermal wall.

In the middle of the day when thermals are at their

strongest, the thermal wall can be very distinct and

violent, yet in the morning and late evening much softer.

Keeping this in mind, the main objective is to make

sure you are completely inside the thermal. This is

called centering or coring the thermal. You will need to

constantly make adjustments to stay in the center of the

thermal. Keep checking you are getting an even climb

all the way around each circle flown, as you may not be

completely centered in the thermal. Often, especially if

it is a windy day, thermals will drift with the wind. Most

will travel directly downwind. One thing to remember is

your model will also drift with the wind, especially when

circling. Thus, once you have established the core of the

thermal, your model will naturally drift with the thermal,

much the same as a free flight model will. One mistake

people often make is that they don’t allow their model to

drift with the thermal, which causes them to fall out of

the front or side of the thermal as it drifts downwind. If

this happens, then you need to look again and re-acquire

the thermal.

in-Flight adjustments for

performance and conditions

• Pitch Attitude

• Minimum Sink Speed

• Maximum Lift/Drag (L/D) Speed

• Best Penetration Speed

Once the fundamentals of launch, trim and control of

the model are learned, it’s time to consider getting the

most out of its ability to perform. To do that, you must

learn how to trim your model for maximum performance,

whatever the current conditions are at the time. The key

to trimming for maximum performance is to become

knowledgeable about, or aware of, three key speeds:

minimum sink, maximum lift/drag (L/D) and best

penetration.

These three speeds are what we call airspeeds, not

ground speeds (the aircraft’s speed across the ground).

Thus, the airspeed of the plane is relative to the air

mass surrounding it.

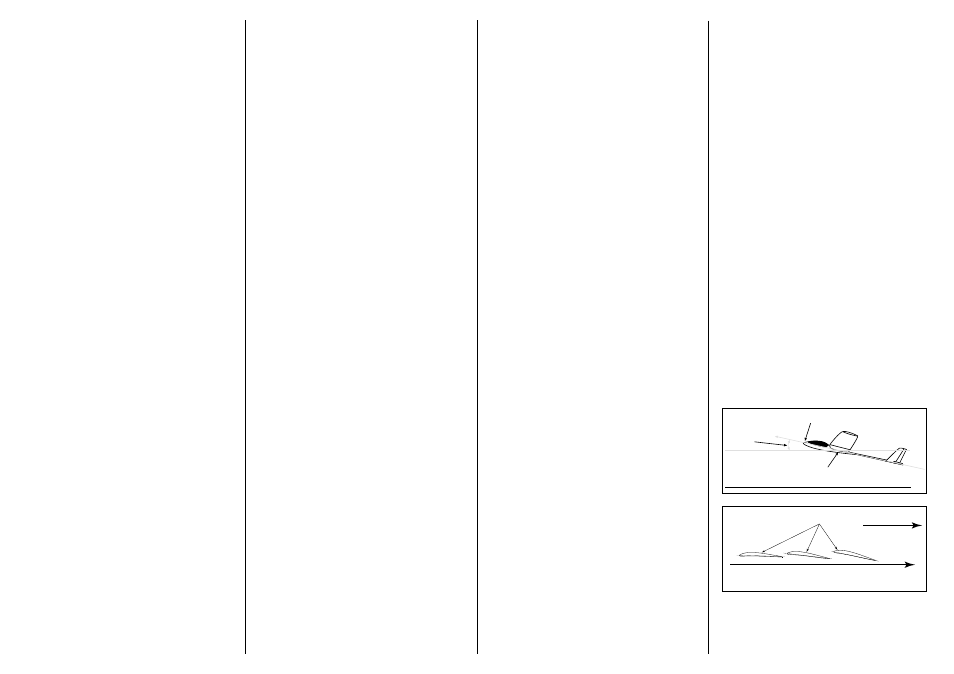

Pitch attitude

To determine the airspeed, you will have to watch

carefully for its pitch attitude. Pitch attitude can best

be described as the amount (degree) the nose of the

aircraft is above or below a line relative to the horizon.

The angle of attack term is used to describe the angle

between the chord (width) of the wing and the direction

the wing moves through the air.

Pitch

Attitude

Longitudinal

Axis

Nose

Center of

Gravity

Horizon

Line Relative to Horizon

Relative Wind Direction

Increasing Angle of Attack