Experiment #39: radio announcer – Elenco Electronic Playground 50-in-1 Experiments User Manual

Page 58

-58-

Now that you’ve built an AM receiver, how about building

an AM transmitter? Ever wanted to be a radio

announcer? You’re about to get your chance. Note: you

need an AM radio for this experiment.

Connect the wires according to the Wiring Checklist,

connecting the battery wire last since this will turn on the

circuit. As in the last experiment you will get better circuit

performance if you keep your wires short, so don’t use

longer wire lengths than you need to.

Take an AM radio you have in your home, turn it on,

extend its antenna, and place it next to your Electronic

Playground. Tune it to the low end of the AM frequency

range or somewhere near the low end where there is only

static and no radio station. Now slowly adjust your

variable capacitor until you hear the static quiet down or

you hear a hum instead. This indicates to you that your

radio is receiving the transmitted signal from your

Playground, so both must be on the same frequency. Tap

the cardboard panel near the speaker, you should hear

this on the radio. Turn the radio volume control up a little

if you don’t hear it at first. If you can’t get your radio and

Playground to be on the same frequency then try tuning

the radio to a different frequency (stay near the low end

of the radio’s tuning range) and try again. The AM

transmitter circuit you are using is a very simple one and

it will not operate across the entire range of AM radio

frequencies. Your radio may have been tuned to a

frequency that your transmitter can’t reach. You can also

tune your radio while tapping near the speaker. When

you hear the tapping then your Playground and radio are

on the same frequency (if this happens to be where an

AM station exists then tune Playground and radio to the

nearest static spot). If you still can’t get this to work then

check your circuit wiring. This is the most complex circuit

you will build, and it is easy to make wiring errors.

Now talk into the speaker, keeping your mouth close to it.

You should hear yourself on the radio! Turn up your radio

volume control or shout if you don’t hear yourself at first.

You can also adjust your variable capacitor slightly to

make sure you are tuned for best transmission.

In this experiment the speaker is being used as a

microphone. A microphone is the opposite of a speaker,

converting sound waves into electrical energy by sensing

the variations in air pressure. (Recall from Experiment 27

that sound waves are variations in air pressure). The

mechanical construction of the speaker allows it to also

be used as a microphone, though it is more efficient as a

speaker than as a microphone. If your voice didn’t sound

very clear on the radio, it is probably because of the

speaker’s limitations as a microphone. The transformer is

used with the speaker as before.

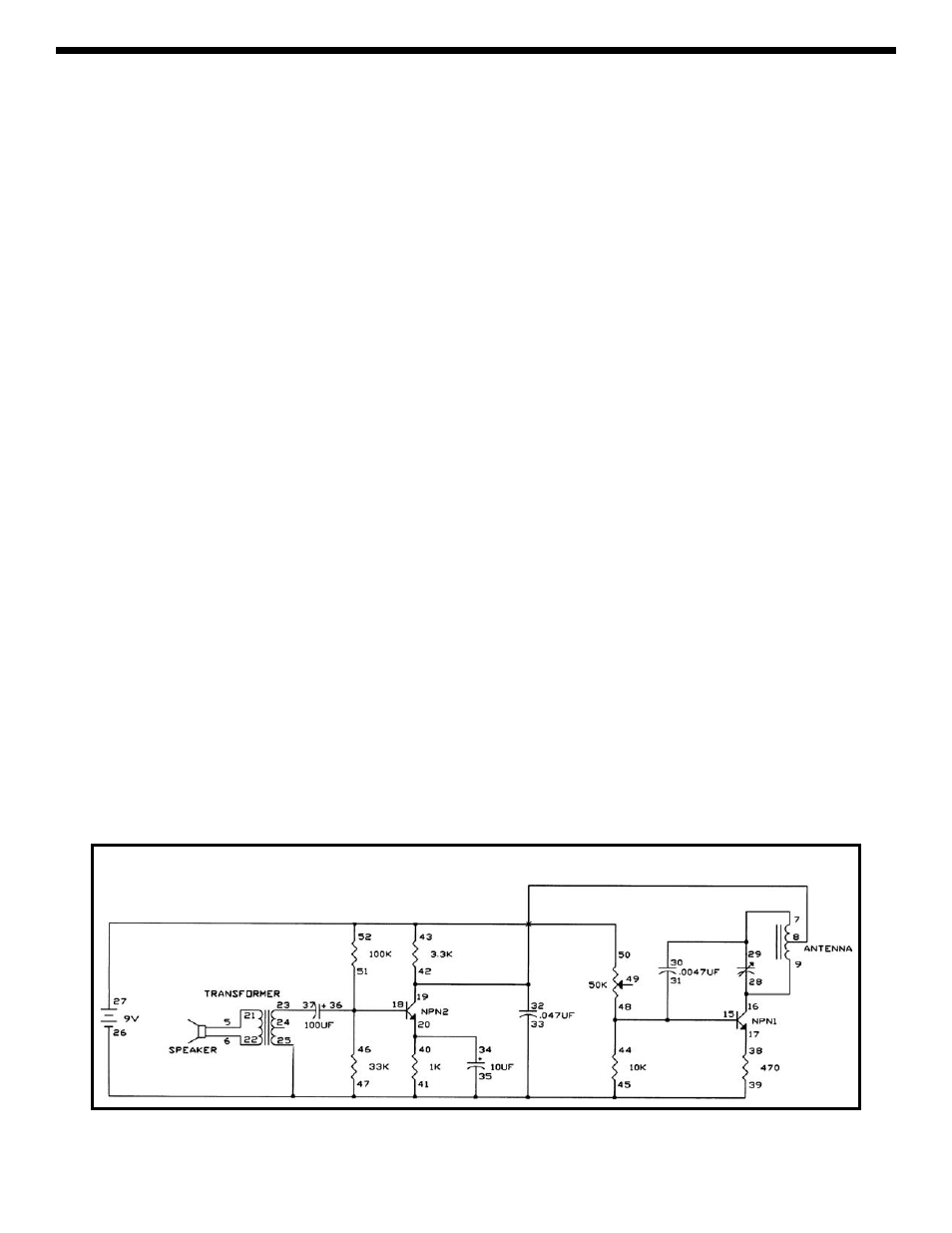

The circuit is complex but advanced students may want

to take a look at the schematic. The signal from the

speaker (microphone) and transformer is applied to a

high gain amplifier built around NPN2. This is the

standard application of the transistor circuit you used in

Experiment 16. The four resistors turn on the transistor

but do not saturate it. The circuit built around transistor

NPN1 is an oscillator, similar to the ones you have been

using only higher in frequency. It uses the antenna as its

inductor instead of the transformer, uses the variable

capacitor to adjust the frequency, and it uses four

resistors (including the 3.3K

Ω) to turn on the transistor

without saturating it. It also gets its power from the output

of the NPN2 circuit instead of directly from the battery.

This is how the high-frequency oscillator is amplitude

modulated to carry your voice to the radio. Part of the

oscillator energy is transferred into the air at the antenna.

Now you can use this circuit to be a radio announcer or

DJ!

EXPERIMENT #39: Radio Announcer

Schematic